Tiki: A California Invention

Tiki culture as we know it was invented in Hollywood — couldn't have happened anywhere else. And for added fun, the real mai tai recipe.

This article originally appeared on Serious Eats about nine years ago. It was edited by Maggie Hoffman. A while back some dorks bought the site and removed a number of longer pieces, including this one. So I'm reclaiming it. I've also updated it. —Katherine

Tiki culture as we know it was invented in Hollywood — couldn't have happened anywhere else. The founding father was a bootlegging fabulist known as Don the Beachcomber who became friends with producers and actors by consulting on movies set in the Pacific; he said he had lived in the South Seas and therefore had first-hand experience, but that's almost certainly not true. He brought Navy Grog and rumaki to the swell set through a series of tall tales about rum's purity (it was actually just the cheapest booze) and "the Orient's exotic flavors" (you know, soy sauce and brown sugar).

Though Trader Vic’s, the tiki chain that started in Oakland, California, will tell you that their founder Vic Bergeron created the mai tai* in 1944, all credit for tiki — everything from the theatricality of the service to the reliance on rum to the co-opting of Pacific Islander spirituality — goes to Ernest Gantt, the man who would legally change his name to Don (sometimes Donn) Beach after inventing the craze that introduced many Americans to Asian food and Hawaiian tradition and still has legions of devoted followers. That is, Gantt gets all credit that doesn’t go to his more ambitious ex, who in L.A. went by the name Sunny Sund.

(I realized while researching that "beachcomber" used to be a derogatory term, which adds a whole new level of strangeness to the father of tiki. Here's more and more and more.)

Tiki’s California-elegant origins owe a lot to celebrity culture, the artists and decorators who worked on both movie sets and restaurant builds, and Los Angeles’ prime Pacific Rim location. It survives thanks to innumerable people who just enjoy a powerful drink and a pupu platter.

Gantt opened Don’s Beachcomber Cafe in Hollywood in 1933. In 1937 he moved to a larger location across the street, one with a kitchen. His celebrity friends made it part of their rotation, and he served them extremely potent inventions like Zombies and Navy Grog, each made with several different types of rum plus a cabinet full of other additions. (Imagine how mind-blowing these drinks were in the ‘30s, when a standard cocktail had two, maybe three ingredients in total.)

It must be noted that while Gantt created tiki, his business partner and sometime-wife, Sunny Sund, was the true brains of the business. A 1948 Saturday Evening Post article (found in segments on this tiki enthusiast board) ostensibly about the Don the Beachcomber restaurant that’s really more about Sunny reveals how it wouldn’t have lasted without the “long-gammed, deep-bosomed blonde” behind the wheel. She was a party girl, but she’s the one who really turned tiki into an empire, as Gantt left town when Don the Beachcomber became too much of a legitimate business, even though Sund had always allowed him to keep up tricks like standing on the roof with a hose to trick diners into thinking it was pouring rain outside, so they'd stay for another round.

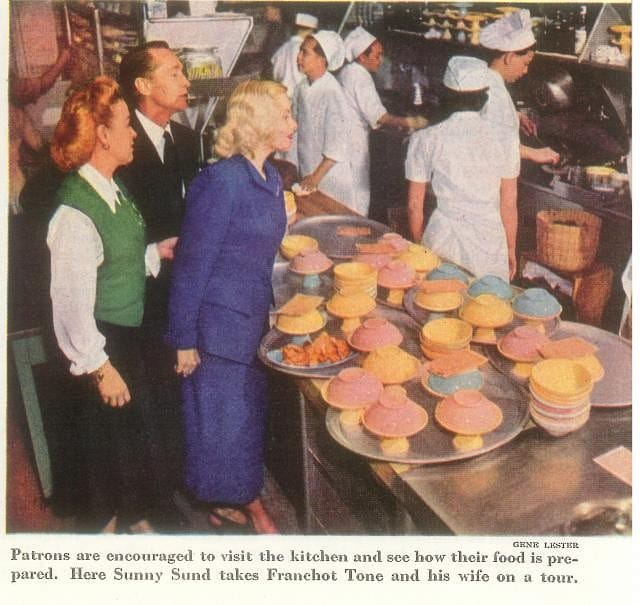

Sund drummed up the initial restaurant investments and hired a chef to cook Chinese food — we’d call it Chinese-American now — that was sophisticated for the era, something that’s often forgotten when we look back now with our more worldly eyes. (Trader Vic’s started serving “island-style” food around the same time, but Don the Beachcomber’s menu was the more specifically “foreign” one.) There was a full-time menu adviser on staff to help diners understand the offerings. Sund’s team installed porthole windows in the kitchen doors that they encouraged guests to peer into. (From the Saturday Evening Post article it's clear that in 1948 it was, apparently, assumed that readers would find Chinese food strange and suspicious. Indeed, the kitchen windows were installed to assuage any fears that the cooks were up to something nefarious with their woks.)

In the beginning, when the restaurant was a celebrity hotspot, this was a classed-up joint: Men had to wear coats, and there were, by Sund’s edict, no cigarette girls, the proto-Hooters girls that were popular at the time. Don the Beachcomber “was made famous by its early customers, who included Howard Hughes, the Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Orson Welles … Their patronage kick-started the whole 40-year tiki craze,” says tiki historian Jeff ‘Beachbum’ Berry. Adds Bosko Hrnjak, the premier Polynesian Pop artist and ceramicist working today, “Hollywood made Don’s. It was an instant hit with the celebrities when it opened; once they discovered it everyone else wanted to get in.”

Don the Beachcomber capitalized on its celebrity clientele, keeping a curio cabinet full of chopstick holders labelled with the users’ famous names. Still, “there was nothing tacky about [tiki bars],” says Berry. “They were regarded as ‘big nights out’ to which patrons ... wore their finest evening clothes.” And the tiki joints made it worth the effort: “Many of the restaurant interiors were designed by moonlighting movie art directors and production designers. The interior design often cost what in today's money would have been millions of dollars per restaurant.” Hrnjak says that employees of the original tiki bars remember it as “a very glamorous era.”

Given the elegance of the original tiki restaurant, it’s notable that tiki often now has downmarket connotations. Hrnjak reports that “Andy Warhol loved the New York location [of Trader Vic’s]. I guess that would be about when the kitsch factor slowly began to take over.”

“The cheap, kitschy reputation came after the ‘golden age’ ended in the late 1970s, when only places without high overhead could stay in business, usually the more casual, ‘beach-bar’ joints that served slushy drinks with cheap ingredients,” says Berry.

Tiki is on the upswing lately, but some new bar owners are still a little hesitant to embrace the mid-century aesthetic. A restaurant in San Francisco called Liholiho Yacht Club whose opening menu included beef-and-fried-oyster lettuce cups and a banana-flavored cocktail, but demands that the media “just don’t call it tiki.”

But tiki was, and still can be, so much more than kitsch. First, the food: a lot of Americans, certainly among the food nerd set, can now differentiate between Thai and Malaysian food, or Mandarin and Hunan dishes. But in the ‘30s, Don the Beachcomber was opening up a whole new culinary world when it served short ribs, pot stickers, and egg foo young to its guests. Sund had to import ingredients like oyster sauce directly from China, and she called her menu Cantonese, which was a sophisticated nuance for the time. This passage from the Saturday Evening Post feature offers us a lot of insight into the food culture Sund was working within:

Among the former schoolmarm’s first moves was the hiring of a Chinese chef. With Don and the chef, she set to work to devise a South Seas-Cantonese cuisine to outdo any cuisine ever tasted in the South Seas or Canton. The average diner-out partakes of Chinese food only once in a while, and does it then as a kind of daring lark. Don and Sunny made up their minds to change ‘once in a while’ to frequently, and to eliminate the ‘daring.’ The usual victuals Chinatown dishes up for Americans are composed largely of celery and bean sprouts, both inexpensive. Don and Sunny decided to use chicken, water chestnuts, and bamboo shoots with a lavish hand, although the latter two items had to be imported from China and are costly. They also began to import oyster sauce, wild-plum sauce, lotus nuts and lichee nuts from China, and issued a ukase that there would be no chop suey and chow mein on their menus. Sunny Sund and Don decided that only the best shrimp — the kind known as ‘fifteen count’ — would be used for their fried shrimp.

Secondly, tiki drinks, when made right, certainly fit into the category of craft cocktails. They’re a purposefully-calibrated mix of juices and (usually more than one) liquor, invented with purpose and passion, and each has a traceable history: Berry wrote an entire book about the trade routes and ingredients that led to the mai tai. As for the juices, "Don and Vic — and all decent restaurant/bars that imitated them — always used fresh lime and lemon, at the very least,” says Berry, noting that they also both used fresh diced pineapple in some drinks. At bars like the Tonga Hut in North Hollywood (my personal favorite), each bartender has their own drink menu, and they’re all slapping mint with the best of the mixologists.

Though Tonga Hut can’t claim to be the most storied tiki bar in Los Angeles — that would be Tiki Ti, which was opened in 1961 by a former employee of the original Don the Beachcomber — it is the oldest still-operational one (opened in 1958). The jewel of Palm Springs is a tiny, gorgeous little cave called Bootlegger Tiki has opened in the exact location where a Don the Beachcomber once stood. It is decorated with black velvet paintings, but they have worked some sort of nightlife magic and made the place seem upscale nonetheless. Downtown Disney's Trader Sam's is perfection (sit inside, though, for the tiki part of the experience), and I'm deeply interested in checking out Strong Water Anaheim; Lucky Tiki looks interesting.

These new bars speak to tiki’s staying power. Yes, at first glance tiki might seem a little silly, as though the word kitschy were invented specifically to describe tiki culture. And it’s true that some people associate tiki with lesser, animatronic-infested Disneyland bars. But Disney was just taking ideas from L.A.’s coolest bars and restaurants when he brought automated rain showers to his playground.

Tiki has a well-documented history. Is it authentic? In a sense, yes: it is a genuine expression of the cross-cultural pollination of SE Asia, Hawaii, and the west coast of the United States, from just after WWI to Hawaii’s first years of statehood. Add to that fun food and complicated drinks, and we’ve got a bar scene for the ages.

*Mai Tai recipe

3/4oz fresh lime juice (I get it by the gallon at LAX-C in Chinatown.)

1/4oz simple syrup (or rich simple syrup, which adds a touch of vanilla)

1/4oz orgeat (almond syrup)

1/2oz curaçao (preferably dry)

2oz aged rum (The variety Trader Vic used no longer exists, but try to get a blended, aged rum.)

Shake or stir with plenty of ice. Then double the ice. Garnish with a half lime shell and a sprig of mint, if you like.