An Early L.A. Catering Truck With Great Timing

Of course, in the American style, it eventually turned into the "jam something in your piehole quick" food culture we have here.

Continuing with our series on real-life eating places depicted on "Columbo," in season one, episode seven, there is a catering truck parked at a downtown site of construction and murder. It's not part of the plot at all, but it's on camera long enough for us to read the name: "Canale Foods."

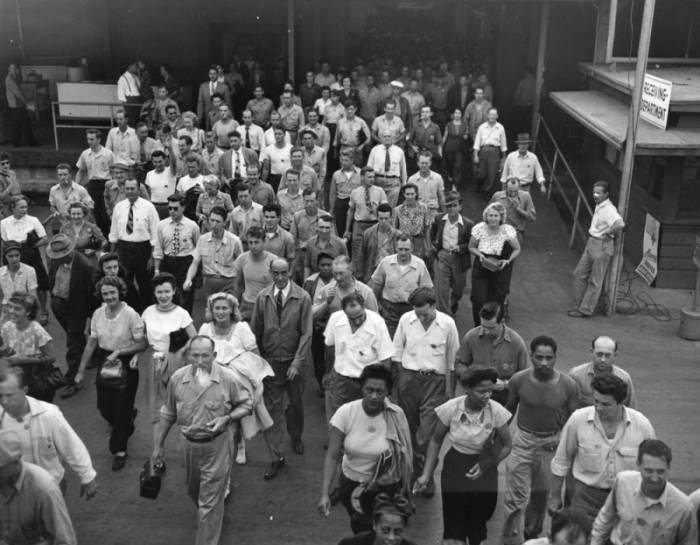

The truck was (or represented) one of a fleet started by Luigi Canale in the mid 1940s. After serving in WWII, Canale set up shop in Los Angeles with his wife. She made sandwiches and cookies, he took them to factories to tempt workers on their breaks. Eventually he went from foot to wheel, and sent a number of "portable snack counters" to workplaces around the county.

Canale's timing was pretty great, as workers around the country attained mandated breaks, and, in a situation pretty particular to Los Angeles, crafts services (later craft service) started to specifically mean food service. Food vendors with pushcarts or horse-drawn wagons had existed for centuries, but I think these snack trucks mark the beginning of food truck culture in L.A. (Credit usually goes to Raul Martinez, founder of King Taco; he opened his taco truck in 1974. I'd say he didn't invent the concept, he perfected the form.)

Traditionally, everyone involved in Hollywood studio productions brought their own refreshments to set. That evolved eventually, and everyone would end the day by putting money in a can, and one person would provide the next day's coffee and doughnuts. The current craft service tables evolved from the decision to have IATSE Local 80 take over food (separately from outside caterers), since those union members did and do such varied work anyway. (Click the Smart Mouth links below for more on that history.)

Employees weren't always guaranteed breaks, but California added them to the labor laws in 1945. They're a result of groups with very disparate goals all wanting the same thing.

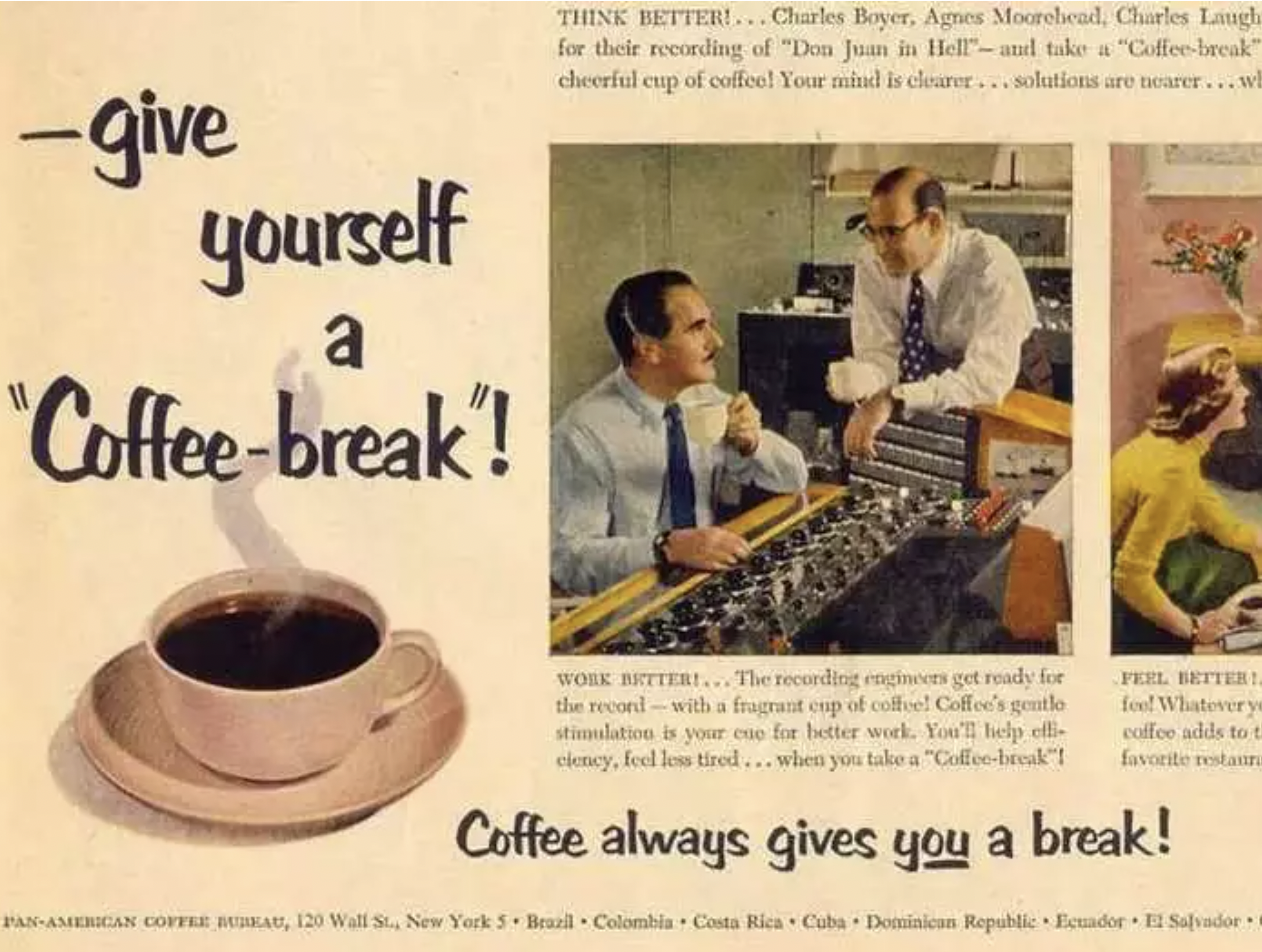

Labor wanted breaks for breaks' sake. Perfectly reasonable. Factory owners wanted workers quick and alert, to bring more money in. And the coffee industry, which was spending money on advertising and hiring evil psychologist John B. Watson to create its campaigns, wanted to sell more beans. There was even a lawsuit in 1955 where a factory owner tried to make coffee breaks mandatory for employees, but refused to pay them for time spent sipping. (He lost, but only on appeal.)

American coffee breaks probably emerged from Nordic traditions, where an afternoon caffeine-and-pastry time is practically a sacred time. Let me quote myself:

The story goes that a lot of Norwegian immigrants arrived in Stoughton, Wisconsin in the 1800s to work in a particular wagon factory. There was also a tobacco factory in town, and the owner reached out to the wagon worker’s wives to work for him. They collectively agreed to the job, with the condition that they could go home twice a day to rest and have coffee. There’s now a yearly event in Stoughton called the Coffee Break Festival and Car Show.

Of course, in the American style, the coffee break merged into the "jam something in your piehole quick" food culture we have here. That's sad, because when the Canales started selling their homemade cookies, they probably had something less panicky in mind for their customers.

History of craft service:

More "Columbo"-inspired histories: